Date: October 3, 2025 — Global

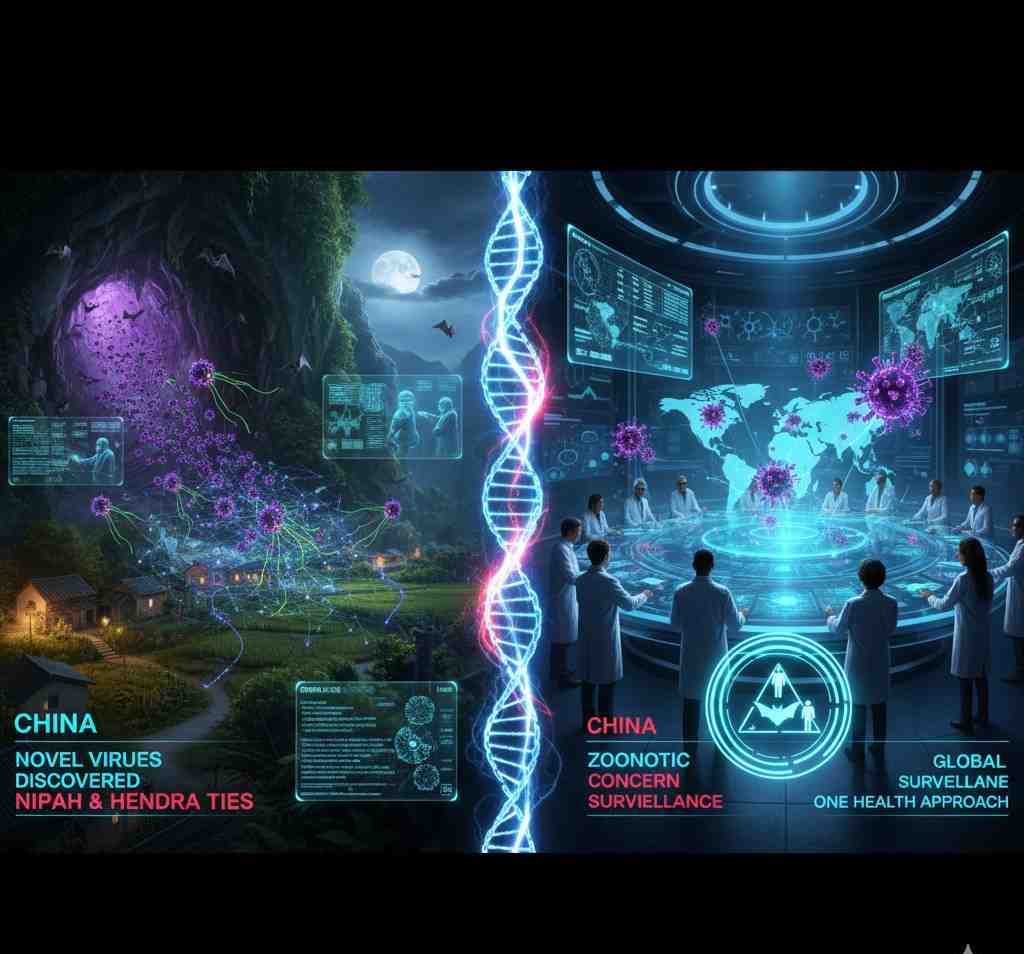

In a development that underscores the fragile boundary between animal and human health, a team of virologists in China has discovered a group of previously unknown viruses in bat populations inhabiting regions close to human dwellings. Among these newly identified viruses, two display close genetic ties to Nipah and Hendra viruses — pathogens known for causing severe respiratory and neurological illnesses in humans.

🔍 Discovery at the Interface of Wildlife and Human Habitation

The research focused on bats residing near orchards, caves, and rural settlements — areas where wildlife and human activity overlap. Field teams collected biological samples from bat colonies, performing deep sequencing to screen for viral genetic signatures. The analysis revealed multiple novel viral sequences, some of which fall into families capable of infecting mammals.

What makes the findings especially concerning is that some of these new viruses share structural similarities with Nipah and Hendra viruses — both of which are known to cross species barriers and cause potentially fatal disease in humans. The new viruses, while not proven to cause human disease yet, warrant close surveillance and further investigation.

🦠 Zoonotic Potential and Public Health Implications

Researchers emphasize that spillover from animals to humans is complex and depends on multiple factors — like viral load, host receptor compatibility, human exposure behaviors, and environmental conditions. Still, these new bat viruses are being classified as viruses with zoonotic potential, meaning they may pose a risk of crossing into humans under the right circumstances.

Virologists caution that detecting a virus in bats is not equivalent to an active human threat. However, the discovery serves as an early warning: pathogens residing in wildlife reservoirs may evolve, adapt, and eventually breach into human populations.

🧪 What We Know About the Viruses So Far

- The viruses were detected via genomic sequencing, followed by bioinformatic analyses to compare them to known viral databases.

- Preliminary genetic comparisons suggest that viral genes involved in cell entry and replication bear resemblance to those found in Nipah and Hendra.

- Laboratory work is now underway to examine whether these viruses can infect mammalian (and ideally human) cell lines under controlled conditions.

- Researchers intend to map the receptors used by these viruses and assess their ability to jump species barriers.

🚨 Surveillance, Preparedness & Next Steps

Public health agencies and international virology networks are being alerted to monitor for any unusual human illnesses in areas near the sampling sites. Steps being taken include:

- Enhanced surveillance in human communities neighboring bat habitats, looking for unexplained fevers, respiratory or neurological syndromes.

- Serological surveys to check if people living nearby have antibodies against these new viruses — which would indicate past exposure.

- Laboratory infectivity studies to see whether the viruses can replicate in human or mammalian cells.

- Ecological and behavioral mapping to understand how and when humans might come into contact with bat secretions or excreta.

- Public communication to educate local populations about risk reduction — such as avoiding direct contact with bats, using protective equipment when entering caves or handling wildlife, and improving livestock biosecurity.

🌍 Broader Lessons & Outlook

This discovery is a reminder that humanity is still coexisting with a vast unseen microbial world. Many pathogens that infect humans likely originate from wildlife, and our expanding footprint into natural habitats increases the chances of encounters with novel viruses.

The current situation underscores the importance of the One Health approach: combining human, animal, and environmental health strategies to detect and prevent zoonotic disease emergence. Investments in field surveillance, molecular diagnostics, and rapid response protocols are more critical than ever.

While the newly discovered bat viruses are not yet proven to infect humans, their detection provides a vital early alarm — giving scientists and public health systems a head-start in anticipating and preventing the next potential spillover event.