I. Introduction to the Thyroid Gland

A. Anatomy of the Thyroid Gland

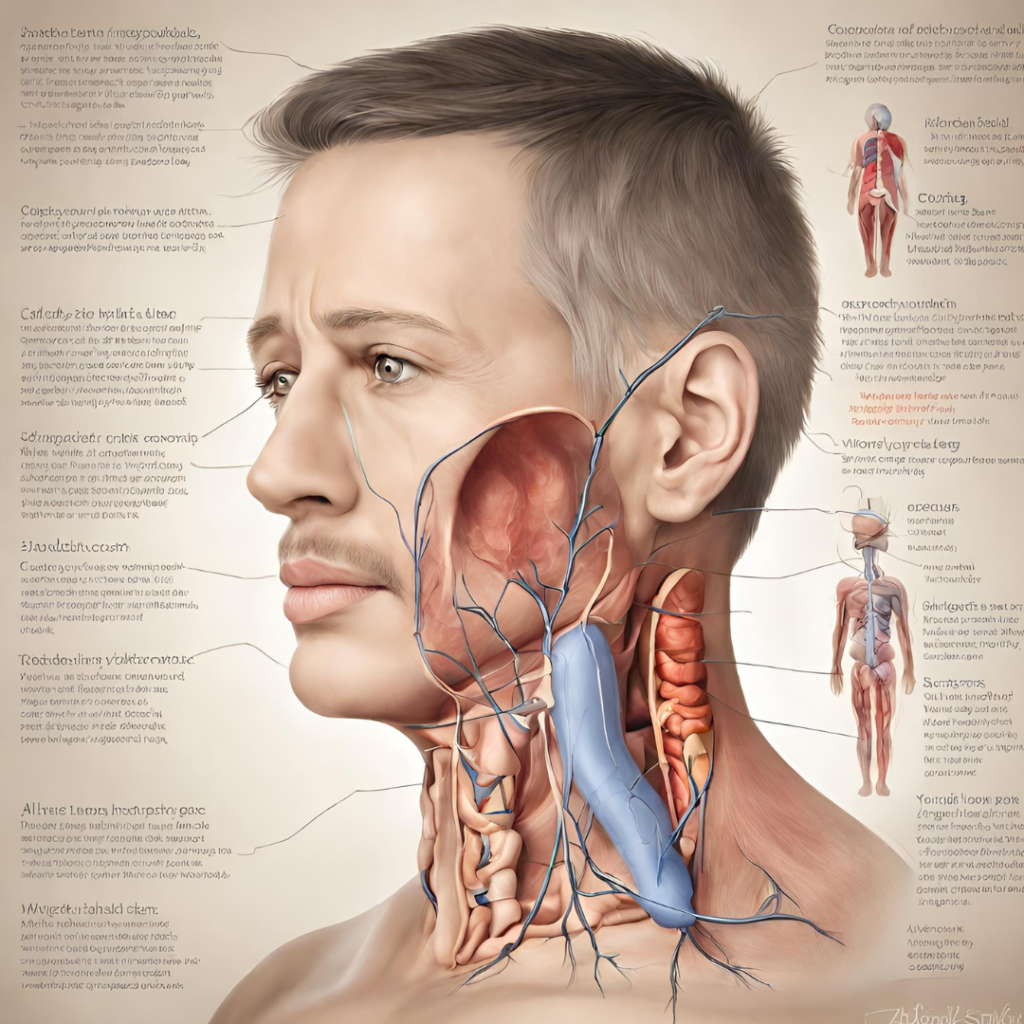

- The thyroid gland is a highly vascularized organ located in the anterior neck, just below the larynx.

- It consists of two lobes connected by a narrow isthmus, and its size can vary considerably among individuals.

- Each lobe is composed of numerous follicles, which are spherical structures lined with follicular cells that produce thyroid hormones.

- The thyroid gland receives its blood supply from the superior and inferior thyroid arteries, which provide oxygen and nutrients necessary for hormone synthesis and secretion.

- Nerves from the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems innervate the thyroid gland, regulating its activity and responsiveness to hormonal signals.

B. Function of the Thyroid Gland

- Regulation of Metabolism: Thyroid Gland hormones play a crucial role in regulating metabolic processes throughout the body, including energy production, lipid metabolism, and protein synthesis. They increase basal metabolic rate (BMR) by stimulating oxygen consumption and heat production in cells.

- Role in Growth and Development: Thyroid Gland hormones are essential for normal growth and development, particularly in infants, children, and adolescents. They promote linear growth, skeletal maturation, and brain development, influencing cognitive function and neurological outcomes.

- Influence on Body Temperature: Thyroid hormones help regulate body temperature by modulating heat production and dissipation mechanisms. They affect thermogenesis, sweating, and blood flow to the skin, maintaining thermal homeostasis in response to environmental and physiological stressors.

- Impact on Energy Levels: Proper Thyroid Gland function is necessary for maintaining energy balance and vitality. Thyroid hormones affect energy expenditure, physical performance, and subjective well-being, with imbalances leading to symptoms such as fatigue, weakness, and lethargy.

C. Importance of Thyroid Hormones

- Thyroxine (T4): The predominant hormone produced by the thyroid gland, T4 serves as a prohormone that is converted into the more biologically active hormone triiodothyronine (T3) in peripheral tissues. T4 is synthesized and secreted by follicular cells in response to thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) released by the pituitary gland.

- Triiodothyronine (T3): T3 is the active form of Thyroid Gland hormone responsible for mediating cellular responses to thyroid stimulation. It regulates gene transcription, protein synthesis, and mitochondrial function, influencing metabolic rate, thermogenesis, and energy expenditure.

- Calcitonin: Produced by parafollicular cells (C cells) within the thyroid gland, calcitonin helps regulate calcium homeostasis by inhibiting osteoclast activity and promoting calcium deposition in bone tissue. It plays a minor role in calcium metabolism compared to parathyroid hormone (PTH) secreted by the parathyroid glands.

II. Thyroid Disorders: Overview

A. Hypothyroidism

- Causes and Risk Factors: Hypothyroidism occurs when the thyroid gland fails to produce an adequate amount of thyroid hormones, resulting in a slowing of metabolic processes and systemic effects. Common causes include autoimmune thyroiditis (Hashimoto’s thyroiditis), thyroid surgery, radioactive iodine therapy, iodine deficiency, and certain medications (e.g., lithium, amiodarone).

- Signs and Symptoms: Hypothyroidism can manifest with a wide range of symptoms, including fatigue, weight gain, cold intolerance, constipation, dry skin, hair loss, muscle weakness, depression, and cognitive impairment. Symptoms may vary in severity and may develop gradually over time.

- Diagnosis and Laboratory Tests: Diagnosis of hypothyroidism is confirmed through blood tests measuring Thyroid Gland-stimulating hormone (TSH), free thyroxine (T4), and sometimes triiodothyronine (T3) levels. Elevated TSH and decreased T4 levels are characteristic findings consistent with primary hypothyroidism.

- Treatment Options: Hypothyroidism is typically managed with synthetic thyroid hormone replacement therapy to restore hormone levels to normal. Levothyroxine is the most commonly prescribed medication and is taken orally once daily on an empty stomach. Dosage is titrated based on clinical response and thyroid function tests.

B. Hyperthyroidism

- Causes and Risk Factors: Hyperthyroidism results from excessive production of thyroid hormones by the thyroid gland, leading to a hypermetabolic state and systemic effects. Common causes include Graves’ disease, toxic multinodular goiter, toxic adenoma, subacute thyroiditis, and excess iodine intake.

- Signs and Symptoms: Hyperthyroidism is associated with a constellation of symptoms, including weight loss, tachycardia, palpitations, heat intolerance, sweating, tremors, anxiety, insomnia, and proximal muscle weakness. Patients may also present with goiter, thyroid nodules, or ophthalmopathy in Graves’ disease.

- Diagnostic Tests: Diagnosis of hyperthyroidism is confirmed through blood tests measuring TSH, free T4, and free T3 levels. Decreased TSH and elevated T4 and T3 levels are characteristic findings consistent with primary hyperthyroidism.

- Treatment Approaches: Treatment options for hyperthyroidism aim to reduce thyroid hormone production and alleviate symptoms. Antithyroid drugs (e.g., methimazole, propylthiouracil) are commonly used to inhibit thyroid hormone synthesis, while radioactive iodine therapy and thyroidectomy may be considered for definitive treatment.

C. Thyroid Nodules

- Types of Thyroid Nodules: Thyroid Gland nodules are discrete lesions or growths within the thyroid gland that may be palpable on physical examination or detected incidentally on imaging studies. They can be solitary or multiple and may be benign (non-cancerous) or malignant (cancerous).

- Evaluation and Diagnosis: Evaluation of thyroid nodules involves a comprehensive assessment to determine the risk of malignancy and guide management decisions. Diagnostic modalities include thyroid ultrasound, fine-needle aspiration biopsy, molecular testing (e.g., gene expression profiling), and radionuclide imaging (e.g., thyroid scan, positron emission tomography).

- Management Options: Management of thyroid nodules depends on factors such as size, appearance, and risk of malignancy. Options include observation with serial ultrasound monitoring, thyroid hormone suppression therapy, fine-needle aspiration biopsy for cytological evaluation, radioactive iodine ablation, or surgical excision (thyroidectomy).

D. Thyroid Cancer`

- Types of Thyroid Cancer: Thyroid cancer encompasses a heterogeneous group of malignancies arising from follicular or parafollicular cells within the thyroid gland. The most common histological subtypes include papillary carcinoma, follicular carcinoma, medullary carcinoma, and anaplastic carcinoma.

- Risk Factors and Causes: Risk factors for thyroid cancer include exposure to ionizing radiation (e.g., childhood irradiation), family history of thyroid cancer or thyroid nodules, certain genetic syndromes (e.g., familial adenomatous polyposis, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2), and environmental factors (e.g., dietary iodine deficiency).

- Symptoms and Diagnosis: Thyroid Gland cancer may present with a variety of symptoms, including a painless neck lump or nodule, hoarseness, dysphagia, odynophagia, cervical lymphadenopathy, or symptoms of compression (e.g., dyspnea, stridor). Diagnosis is established through a combination of imaging studies, fine-needle aspiration biopsy, molecular testing (e.g., BRAF mutation analysis), and histopathological examination of surgical specimens.

- Treatment Modalities: Treatment of thyroid cancer depends on factors such as histological subtype, tumor size, extent of disease, and patient characteristics. Options include surgery (thyroid lobectomy, total thyroidectomy, neck dissection), radioactive iodine therapy (iodine-131 ablation), external beam radiation therapy, chemotherapy, targeted therapy (e.g., tyrosine kinase inhibitors), and immunotherapy.

These expanded sections provide detailed information on the anatomy and function of the thyroid gland, as well as an in-depth examination of common thyroid disorders, including hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, thyroid nodules, and thyroid cancer. Each subsection covers causes, risk factors, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment options, providing a comprehensive overview of thyroid health. Additionally, incorporating case studies, patient testimonials, expert opinions, and references can further enhance the content and provide valuable insights into managing thyroid disorders effectively.

III. Impact of Thyroid Disorders on Health

A. Metabolic Effects

- Influence on Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR): Thyroid hormones play a crucial role in setting the body’s basal metabolic rate (BMR), which refers to the amount of energy expended at rest. Hypothyroidism is associated with a decrease in BMR, leading to weight gain and difficulty in losing weight, while hyperthyroidism results in an increase in BMR, causing weight loss and increased appetite.

- Effects on Weight Regulation and Body Composition: Thyroid hormones regulate lipid metabolism and adipose tissue distribution, affecting body weight and composition. Hypothyroidism is often characterized by weight gain, accumulation of adipose tissue, and changes in body composition, including increased fat mass and decreased lean body mass. Conversely, hyperthyroidism is associated with weight loss, muscle wasting, and reduced fat mass.

- Metabolic Syndrome and Cardiovascular Risk: Thyroid dysfunction, particularly hypothyroidism, is linked to an increased risk of metabolic syndrome, a cluster of metabolic abnormalities including central obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension. These metabolic changes contribute to an elevated risk of cardiovascular disease, including coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, and stroke, highlighting the importance of thyroid function in cardiovascular health.

- Lipid Metabolism and Atherosclerosis Risk: Thyroid hormones influence lipid metabolism by regulating the synthesis, secretion, and clearance of lipoproteins. Hypothyroidism is associated with elevated levels of total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and triglycerides, as well as decreased levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), predisposing individuals to atherosclerosis and cardiovascular events. Conversely, hyperthyroidism may lead to reduced levels of total cholesterol and LDL-C, but it can also cause dyslipidemia characterized by elevated triglycerides and decreased HDL-C, contributing to cardiovascular risk.

B. Neurological and Psychological Effects

- Cognitive Impairment and Memory Dysfunction: Thyroid hormones play a critical role in cognitive function, learning, and memory processes. Hypothyroidism is associated with cognitive impairment, including deficits in attention, concentration, memory, and executive function, as well as psychomotor slowing and depression. These cognitive changes may be reversible with thyroid hormone replacement therapy but can have a significant impact on quality of life and daily functioning. Conversely, hyperthyroidism may cause cognitive symptoms such as irritability, anxiety, and emotional lability, as well as difficulty concentrating and maintaining attention.

- Mood Disorders: Depression, Anxiety, and Bipolar Disorder: Thyroid dysfunction, particularly hypothyroidism, is linked to an increased risk of mood disorders, including depression, anxiety, and bipolar disorder. Hypothyroidism is associated with depressive symptoms such as low mood, anhedonia, fatigue, and psychomotor retardation, which can mimic major depressive disorder. Additionally, hypothyroidism may exacerbate symptoms of anxiety and panic disorder, leading to increased nervousness, restlessness, and irritability. In severe cases, untreated hypothyroidism may precipitate or exacerbate bipolar disorder, characterized by mood swings between depressive and manic episodes.

- Neuromuscular Symptoms: Weakness, Tremors, and Reflex Abnormalities: Thyroid hormones play a crucial role in neuromuscular function, including muscle strength, tone, and coordination. Hypothyroidism is associated with muscle weakness, fatigue, and exercise intolerance, as well as cramps, myalgias, and stiffness. Additionally, hypothyroidism may cause peripheral neuropathy characterized by sensory and motor deficits, including numbness, tingling, and paresthesias. Conversely, hyperthyroidism may lead to muscle weakness, tremors, and hyperreflexia due to increased sympathetic activity and neuromuscular excitability.

C. Reproductive Health

- Impact on Menstrual Cycle and Fertility: Thyroid hormones play a critical role in regulating the menstrual cycle and reproductive function in women. Hypothyroidism is associated with menstrual irregularities, including oligomenorrhea, anovulation, and hypomenorrhea, as well as infertility and recurrent miscarriage. Additionally, hypothyroidism may impair ovarian function, folliculogenesis, and steroid hormone production, leading to subfertility or infertility. Conversely, hyperthyroidism may cause menstrual disturbances such as oligomenorrhea, amenorrhea, and irregular bleeding due to alterations in gonadotropin secretion and ovarian function.

- Pregnancy Complications: Gestational Hypothyroidism and Hyperthyroidism: Thyroid dysfunction during pregnancy can have significant implications for maternal and fetal health. Gestational hypothyroidism is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes, including preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, preterm birth, low birth weight, and fetal neurodevelopmental abnormalities. Additionally, untreated hypothyroidism during pregnancy increases the risk of maternal complications such as placental abruption, postpartum hemorrhage, and cesarean delivery. Conversely, gestational hyperthyroidism is linked to complications such as hyperemesis gravidarum, fetal tachycardia, intrauterine growth restriction, and fetal thyroid dysfunction.

- Thyroid Dysfunction in Menopause and Andropause: Thyroid disorders can affect hormonal balance and reproductive function during menopause and andropause, the natural transition periods marking the end of reproductive capacity in women and men, respectively. Hypothyroidism is more prevalent in postmenopausal women and may exacerbate menopausal symptoms such as hot flashes, mood swings, and cognitive changes. Additionally, untreated hypothyroidism during menopause may increase the risk of cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, and cognitive decline. Conversely, hyperthyroidism may lead to premature ovarian failure, amenorrhea, and infertility in women, while contributing to symptoms such as heat intolerance, sweating, and weight loss in men.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the thyroid gland plays a crucial role in regulating numerous physiological processes essential for overall health and well-being. Thyroid disorders, including hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, thyroid nodules, and thyroid cancer, can have profound effects on various organ systems and may lead to significant morbidity and mortality if left untreated. Understanding the impact of thyroid dysfunction on metabolic, neurological, psychological, and reproductive health is essential for early detection, accurate diagnosis, and effective management of thyroid disorders.

Metabolic effects of thyroid dysfunction can manifest as alterations in basal metabolic rate, body weight, and lipid metabolism, predisposing individuals to metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. Neurological and psychological symptoms, including cognitive impairment, mood disorders, and neuromuscular abnormalities, can significantly impact quality of life and functional status. Reproductive health may be affected by thyroid dysfunction, leading to menstrual irregularities, infertility, pregnancy complications, and hormonal imbalances.

Diagnostic evaluation of thyroid disorders involves comprehensive assessment of thyroid function through laboratory tests, imaging studies, and fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Treatment approaches vary depending on the underlying thyroid disorder and may include medication management, radioactive iodine therapy, thyroid surgery, and lifestyle modifications. Prevention and public health strategies, including screening guidelines, health promotion, and research initiatives, are essential for raising awareness, improving access to care, and advancing our understanding of thyroid health.

In conclusion, addressing thyroid disorders requires a multidisciplinary approach involving healthcare providers, patients, caregivers, and community stakeholders. By prioritizing thyroid health and implementing evidence-based strategies for prevention, detection, and management, we can optimize outcomes and enhance the overall well-being of individuals affected by thyroid disorders. For More Information you can check our blogs “From Desk to Treadmill: Energizing Strategies for Staying Active in a Sedentary Job”.